Why It Is Difficult to Come Off Antidepressants

I have a lot of patients who struggle with coming off antidepressants, whose withdrawal side effects are often minimized or dismissed. These side effects can be so debilitating that they stay on a low dose of medication that doesn’t work for years because they are afraid of going through the withdrawal again. A lot feel defeated, and are made to think that the last low dose, and why they can’t come off of it, is all in their head. I send this email to my patients so they know it's biological, not psychological, and there is nothing wrong with them; it is the potency of the medication and how the drug works on our brains that is the problem.

If you’ve taken an Antidepressant and have tried stopping, and suffered severe withdrawal symptoms, you probably noticed or felt that the last part of the taper was the hardest. That’s not just your experience; there's a real biological reason behind it.

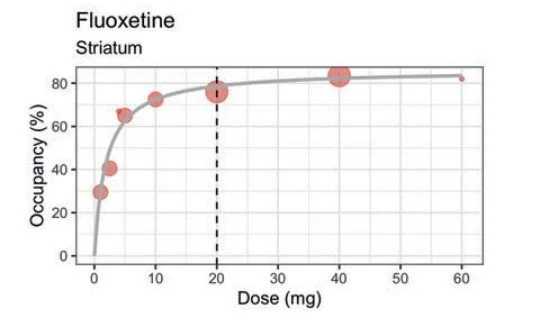

Most people assume the effects of antidepressants work in a straight line with the dose, but they don’t. Most work nonlinearly, meaning even small doses still have a big effect on your brain. The picture below helps explain what is called a hyperbolic curve. When 80% of receptors are occupied by Prozac and all other SSRIs, which, when you look at the graph, is just 30 mg for Prozac, you get a very minimal beneficial response by increasing the dose, but you get a lot more side effects.

At just 10 mg of fluoxetine (Prozac) we block 75% of serotonin transporters in the brain, almost as much as 20 mg (only a 5% increase doubling the dose). Doubling the dose from 20 mg to 40 mg again only increases receptor blockade by 2%. Now work backwards like you are tapering off the drug. Not a big deal until you hit the final dose that is FDA approved in pill form for Prozac: 10 mg. When you drop from 10 mg to zero, you drop off a cliff that is 75 %. That big jump makes the final step of tapering feel so jarring. As you can see, transitioning from high to low doses is easier; however, transitioning from low to no doses can be a significant challenge.

Research shows that reducing an antidepressant dose by more than 25% at once significantly raises the risk of moderate to severe withdrawal symptoms. The acronym to remember them is called: FINISH.

F - Flu-like symptoms: These can include fatigue, achiness, headache, and sweating.

I - Insomnia: This can involve difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or vivid dreams or nightmares.

N - Nausea: This may be accompanied by vomiting.

I - Imbalance: This can manifest as dizziness, vertigo, or lightheadedness.

S - Sensory disturbances: These can be described as "brain zaps," or sensations of tingling, burning, or electrical shocks.

H - Hyperarousal: This can include anxiety, irritability, agitation, or aggression.

These aren't signs your original depression, anxiety, or PTSD is coming back—they're signs your brain is going through antidepressant withdrawal. These symptoms can last weeks to months and are frequently misinterpreted as a "worsening of your mental health condition' and not seen as withdrawal symptoms.

The doses that the drug manufacturers make that are FDA approved, for example, Prozac comes in 60 mg, 40 mg, 20 mg, or a 10 mg tablet, creates large drops in total doses when you step down, going over that 25% threshold that raises the risk for moderate to severe withdrawal symptoms. From 60 mg to 40 mg (33 % drop), then 40 mg to 20 mg (50 %), next 20 mg to 10 mg (50 %), and finally 10 mg to 0 mg .

Because SSRIs reach near-maximum effect even at low doses, yet are manufactured only in widely spaced strengths, each step down removes a big chunk of the drug’s action. That mismatch makes tapering challenging and often triggers uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms. This is why some people need slower tapers or smaller dose steps at the end, like using liquid meds or compound capsules. It's not about being sensitive or weak. It's about respecting your nervous system’s pace. The new trend, backed by science, in de-prescribing/tapering is called hyperbolic tapering. It essentially resembles a long, flat waterslide on a graph, with a gradual ending.

It means the lower you go, the slower you go, and the aim is usually a 10% reduction in your total dose every few weeks. These are designed for people taking the medication for more than 4 to 6 months who have developed a physiological dependence to the medication.

Stopping cold turkey, or even coming off the medication in a month, can put people in withdrawal for weeks and months later. This can lead people to the false belief that they need to go back on medication because their mental health is so poor, when they are really just going through a drug withdrawal.